Table of contents

- Introduction

- What actually counts as disinformation?

- The history of disinformation

- The modern world changes the playing field

- Examples of disinformation campaigns

- Disinformation in warfare

- Fighting disinformation: what is to be done?

Chapter 1 Introduction

Disinformation is by no means a recent phenomenon. Over the last decade, however, we’ve seen a continuous rise in fake news stories. From disinformation regarding terror attacks in the United States, through elections and pandemics, to the war in Ukraine — disinformation campaigns are alive and well.

But what exactly is disinformation? Where does it originate, and — perhaps more importantly — how does it spread?

We’re going to answer those questions and more in this article. We’re also going to discuss the history of disinformation campaigns over the years, as well as point out several examples (and their consequences).

Chapter 2 What actually counts as disinformation?

A disinformation campaign is the deliberate dissemination of false information in order to influence public opinion. They are most often conducted to achieve political goals, although campaigns aimed at discrediting business rivals have also been noted.

It’s important to distinguish between disinformation campaigns and simple fake news. The key point of difference is the scale. Disinformation campaigns are usually long-term and often make use of various (sometimes unrelated) fake news stories or conspiracy theories.

Some far-right disinformation campaigns, for instance, make use of different messaging depending on the audiences they aim to capture: a different slogan for the anti-vaxxers, another for the QAnon crowd — but all ultimately leading to the same conclusion.

Disinformation campaigns are often conducted by large interest groups, sometimes supported by governments. During the Cold War, both the Soviet Union and the United States engaged their respective intelligence agencies in spreading propaganda in their respective spheres of influence. A famous example is the CIA’s funding of anti-communist movements across the Americas, which eventually culminated in the Iran/Contra scandal.

For the purposes of this article, we define disinformation campaigns to be deliberate, long-term efforts to achieve political change through the spread of false information. This is not to be confused with misinformation — which is simply incorrect information. The key difference is the intentionally deceptive nature of disinformation.

Chapter 3 The history of disinformation

Various forms of disinformation have been with us throughout recorded history. One early example of fake news can be found as early as the Old Testament. Historical attempts at disinformation campaigns weren’t usually effective, however. It wasn’t until the late XIX century that we started seeing organised, long-term campaigns aimed at spreading falsehoods to influence public opinion.

A tsarist pamphlet reinforces antisemitism a hundred years onward

One early example of a modern disinformation campaign resulted in the publication of “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion”, a falsified pamphlet purportedly containing the meeting notes of an “international Jewish conspiracy”. This pamphlet was used in tsarist Russia to justify mass expulsion and persecution of Jewish citizens. It was especially effective because it fed off a climate of antisemitism that pervaded most of Europe at that time.

What’s especially chilling about the Protocols is just how well they continued serving their purpose even decades after the tsarist regime was overthrown. Nazi Germany’s propaganda efforts often referenced the pamphlet to justify their treatment of Jewish people.

It has to be said explicitly: the Protocols are a forgery by the tsarist secret police. This is a historical fact. Facts have rarely gotten in the way of a “good” story, however — and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion are still referenced by modern antisemitic conspiracy theorists, such as David Icke.

World War II — disinformation becomes a weapon

The invention of radio and television were extremely beneficial for mass culture. However, since their very inception they were used for disinformation purposes. We all heard of Joseph Goebbels — his understanding of how radio can be used to control public opinions was one of the lynchpins that kept the Nazi regime in power and with wide popular support throughout the war.

His efforts extended to more than just constantly pushing propaganda in Germany. Lord Haw-Haw was the nickname given to an Englishman who made Nazi propaganda broadcasts to the United Kingdom from Hamburg. These broadcasts were part of a wide demoralisation campaign aimed at civilians and soldiers in Allied countries.

This wasn’t an isolated campaign. Imperial Japan prepared similar broadcasts aimed at Allied troops fighting in the Pacific, while Allied governments broadcast their own propaganda aimed primarily at the Germans. It was during World War 2 that modern intelligence agencies first came about, and techniques first developed during the conflict were the foundations they were built upon.

The Cold War puts information warfare into overdrive

The word “disinformation” most likely comes to us from the Soviet Union. The Russian word дезинформация (dezinformatsiya) obtained its current meaning sometime in the 1920s, being coined by Stalin himself, according to some people.

We can’t know for certain whether the USSR was the first government to employ disinformation as a means of warfare, but they certainly were one of the first to master it. The Soviet intelligence apparatus was one of the first in the world to control public opinion both at home and abroad through a very careful management of information.

The Cold War would intensify the relationship between intelligence agencies and mass media. On both sides of the Iron Curtain, dissident movements were provided with propaganda materials and financial help in order to perpetuate narratives. The West used Radio Free Europe to support anticommunist activists in the Soviet bloc, while the USSR broadcast its state-sanctioned message on Radio Moscow.

Chapter 4 The modern world changes the playing field

The collapse of the Soviet Union did not bring with it an end to disinformation campaigns. In fact, the rapid spread of the internet only provided bad actors with a new playing field.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the rapid spread of conspiracy theories proved that the internet was a good vector of disinformation. Think back to how many people thought that “9/11 was an inside job” or that “jet fuel can’t melt steel beams!”

The environment of the early internet gave rise to disinformation influencers such as Alex Jones. Jones is famous for cultivating an audience full of far-right conspiracists who, among other things, believe that terrorist attacks such as 9/11 or the 2012 Sandy Hook shooting were false flag operations carried out by the US government.

He is far from the only online conspiracy influencer. People like him — and, more importantly, the audiences they cultivated — would later provide the substrate for large-scale disinformation campaigns. Jones was one of the very first online celebrities to acknowledge the QAnon movement, for instance, which later culminated in the January 6th attack on the US Capitol.

The rise of social media provided the perfect vector for spreading disinformation. From anti-vaxxers, through flat-earthers, to the people who believe we’re all ruled by reptilian aliens from Zeta Centauri — all of these people found a welcoming home on platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. After all, they drive up engagement metrics, and those always mean bigger profits.

At the same time, social media dramatically changed the way most people engage with and consume news. Many people switched to only reading those articles that come up on their Facebook feed, which are driven by the algorithm. This makes news media subject to its whims — and, as it turns out, the more polarising an article’s title is, the better.

The fact social media users tend to share articles without reading past the headline only exacerbates the problem. As it turns out, you only need to share a legitimate-looking article with a title that confirms your target audience’s biases (for instance, something about adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccination) to spread your message and receive high levels of engagement.

Chapter 5 Examples of disinformation campaigns

Mumsnet becomes a hub for anti-trans hate

“Clickbait” is a term familiar to most of us — but we tend to only focus on its primary definition: “content designed to increase traffic to a website”. While a valid definition, it ignores the other use of clickbait: providing algorithmic reputability to a source.

If links to a given website receive consistently good engagement results, the algorithm tends to push that website to more and more users. This is how LittleThings.com managed to become the fastest growing “news” site on Facebook in 2015. It identified middle-class, older white women as an effective demographic to target on social media. Unfortunately, it also made them one of the biggest spreaders of disinformation.

A site catering to this demographic became the centre of a disinformation campaign targeting trans people. Mumsnet, a popular forum for British mums, became a hotbed for transphobic discussion in 2016. It became crucial in generating and spreading anti-trans talking points, promoting transphobic influencers and politicians, and, ultimately, contributing heavily to a meteoric rise in hate crimes against trans people in the United Kingdom.

The anti-trans rhetoric has spread outside of the UK and is now being used to threaten the rights of trans people elsewhere. In the United States, for instance, over 100 anti-trans bills were introduced in 2021 alone — a grim record. Far-right movements have latched onto the anti-trans rhetoric and now use it as a recruitment tool.

The anti-gender panic

The anti-trans movement stems from an earlier “moral panic” about “gender ideology” that swept Europe in the early-to-mid-2010s. This phenomenon came to us from both religious conservatives in the United States as well as in Russia.

The aim of the anti-gender panic was to prop up support for far-right politicians under the pretence of “protecting children from sexualization”. It worked, too — anti-gender scaremongering featured heavily in the election campaigns all over Europe.

In Poland, it was a common topic of discussion in the leadup to the 2015 presidential and parliamentary elections, which led to far-right parties becoming the dominant political force in the country. The same rhetoric was also deployed during the 2020 elections, with similar results.

The moral panic against “gender ideology” also reinforced discrimination against LGBTQ+ people. In Poland, around a third of the country’s municipalities declared themselves “LGBT-free zones” — areas explicitly hostile towards a perceived “LGBT ideology”, something referred to by president Andrzej Duda in his 2020 re-election campaign.

Identical rhetoric has been used by other authoritarian governments around the world. In Hungary, Viktor Orban has been campaigning against LGBTQ+ rights for the better part of the last decade. In Brazil, violence against LGBTQ+ citizens surged after the election of Jair Bolsonaro.

Cambridge Analytica

While we’re on the topic of elections — let’s talk about the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

In 2016, Facebook exposed the data of 87 million of its users to a Cambridge Analytica employee. The company then used the data to conduct “influence campaigns” for Donald Trump’s presidential campaign through British PR firm SCL Group.

This was possible by an API exploit in the “thisisyourdigitallife” Facebook app created by Aleksandr Kogan, a researcher at Cambridge University. This was possible due to Facebook’s rather loose handling of user data. Following the scandal, the company severely restricted third party access to users and limited its APIs to prevent future breaches of this nature. Further legal regulation, such as the European Union’s GDPR forced other platforms to follow suit.

However, the damage was already done. Before the scandal, Cambridge Analytica boasted about its ability to swing elections — using tactics such as fake news campaigns, honey traps, and bribery accusations.

Read that again: this was a company which offered disinformation campaigns tailored to specific target groups. It’s far from the only one — and social media platforms’ laissez-faire approach to privacy and user security is what allowed them to conduct this work.

An interlude: how social media platforms allow disinformation to proliferate.

The culpability and irresponsibility of social media platforms cannot be ignored. Facebook in particular is responsible for hosting many disinformation campaigns, some of which ended in tragedy.

Coordinated hate speech campaigns conducted on Facebook by far right organisations linked to the Modi government resulted in several violent attacks against Muslims in India, for instance. In a more outrageous case, a disinformation campaign by the Burmese military on Facebook was directly linked to the genocide of Rohingya people in Myanmar, which led to more than 25,000 deaths.

Another platform with ties to the far right is Twitter, whose former CEO and co-founder Jack Dorsey has been repeatedly criticised for his open embrace of extremist politics. The platform’s platforming of former US President Donald Trump is perhaps the most famous example of a social media network knowingly allowing disinformation to be spread — Ivermectin, anyone?

In fact, Twitter has repeatedly demonstrated its far-right bias, allowing known extremists to remain undisturbed on the site, while banning minority users en masse.

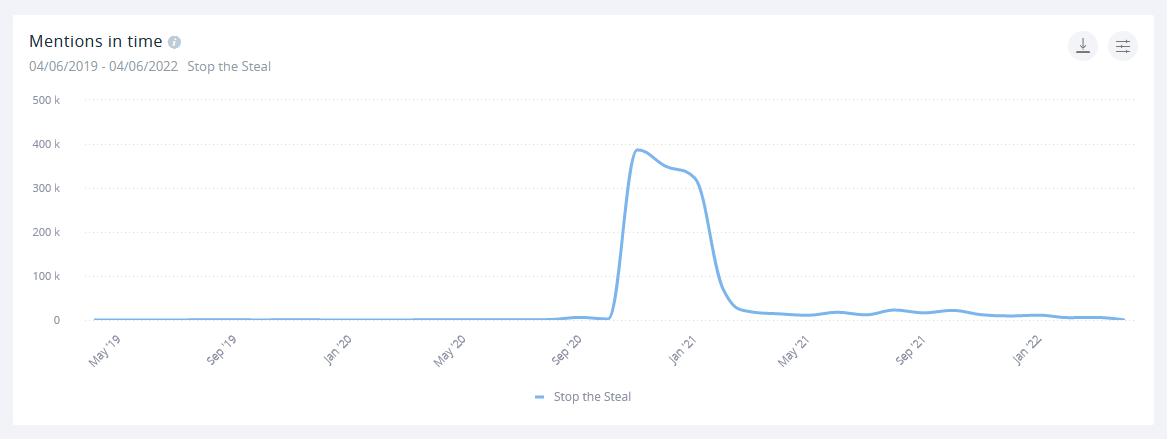

Stop the Steal and January 6th

Twitter and Facebook both played a pivotal role in spreading disinformation that led to the January 6th, 2021 attack on the US Capitol. As we learned from Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen, the company knew about groups spreading “Stop the Steal” disinformation for months leading up to the attack.

The Stop the Steal movement actually dates back to the 2016 US presidential election. Its goal was the same then as it is now: to spread the false narrative that Donald Trump didn’t actually lose the election. Obviously, Trump’s 2016 victory meant the campaign didn’t have to go forward — but that doesn’t mean the influencers behind it sat on their hands for the entire term.

Instead, they used social media to link up with different pro-Trump groups in order to radicalize them to action. QAnon believers, “sovereign citizen” groups, pandemic deniers — everyone was fair game. The campaign strategy was simple: join Facebook groups and use influencers on Twitter in order to spread narratives about the presidential election being “stolen”.

The slogan was rolled out in the leadup to the 2020 presidential election, and it worked. It was boosted by many far-right influencers, chief among them Fox News’ Tucker Carlson and Alex Jones, and was one of the most discussed topics in the American political space. The constant reinforcement of the “stolen election” narrative was successful: on January 6th, 2021, an armed mob of Trump supporters stormed the Capitol building, leading to six deaths.

Chapter 6 Disinformation in warfare

As of the writing of this article, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is ongoing. It is, of course, accompanied by a disinformation campaign — however, it started long before Russian troops started shelling cities. In fact, Russia has been conducting a disinformation campaign aimed at Ukraine ever since the Euromaidan demonstrations of 2013 and 2014.

For those not familiar with the Euromaidan, here’s a quick recap. Following a series of repressive reforms by then-president Viktor Yanukovych, mass protests erupted in Ukraine. Despite heavy crackdowns, the demonstrations succeeded in ousting Yanukovych and marked a significant pro-Western shift in Ukrainian politics.

Yanukovych’s reign has been marked by his pro-Russian policies, culminating in the government’s abrupt decision not to sign the European Union-Ukraine Association Agreement — despite overwhelming support. This was the inciting incident that triggered the initial protests.

In response to a pro-Western government being elected after the Euromaidan, Russia invaded, occupied, and subsequently annexed Crimea and provided support to two separatist republics: Donetsk and Luhansk.

The Russian disinformation campaign about Ukraine

The 2014 invasion marked the beginning of a disinformation campaign targeted at Ukraine. It included all the hits: the Euromaidan was a CIA-led plot (it wasn’t), the new authorities are all neo-nazis (they aren’t, and the far-right coalition got less than 3% of the vote in the 2014 elections), and that Russian-speaking Ukrainians were abused in Crimea (no evidence for that has been presented).

Despite being demonstrably false, these narratives informed Russian policy towards Ukraine over the last eight years. The government-controlled media have been consistently pushing these narratives both within the country and abroad, using outlets such as Russia Today.

Russian disinformation has been spread through outlets not outwardly connected to the Russian government, however. Outlets such as the Grayzone have been used to perpetuate anti-Ukrainian narratives while purporting to present a “left-wing” viewpoint.

The War in Ukraine

The outbreak of the war in February brought with it a heavy influx of new disinformation. Fake accounts appear under news stories and hashtags related to the invasion, spreading disinformation. This is done in hopes of a fake story being picked up and amplified — and thus legitimised — by prominent figures abroad.

This is what happened to the “Ukrainian biolabs” story. According to Russia, Ukrainian laboratories were developing biological weapons with backing from the United States. This is, of course, patently false.

As the old saying goes, however, “never let the truth get in the way of a good story.” The biolabs talking point quickly found fertile ground amongst the QAnon crowd and some segments of the American far right. While the Pentagon was denying any allegations of developing biological weapons in Ukraine, Tucker Carlson was calling that denial a lie on his show, without providing much in the way of evidence.

Sometimes, the story doesn’t even need to be very credible to pick up traction. Footage from the military video game Arma 3 was passed around and claimed as legitimate video from the war. This isn’t a new phenomenon — in fact, Russian media has erroneously used Arma 3 footage to represent military operations in Syria before, while Britain’s ITV has used footage from Arma 2 in a documentary about the IRA.

We’ve also seen deep fake videos used over the course of the war. A viral video purporting to depict Ukrainian president Zelensky talking about surrendering to Russia has surfaced, before quickly being debunked by the actual Zelensky. It has since been removed. The same fate befell a faked video in which Vladimir Putin declared the end of hostilities.

Controlling the narrative: when governments take over social media

A particularly interesting aspect of the Russian disinformation campaign involves its takeover and control of social media networks, primarily TikTok.

Once hostilities started, a new law was quickly passed in Russia, ostensibly to “prevent disinformation”. Using this as a pretext, the authorities banned access to several media organisations. The long-running independent station Echo of Moscow was forced to close its doors. Several other outlets have had access to their websites blocked by Roskomnadzor, the communications authority in Russia.

On March 6th, TikTok announced that in light of these new regulations — which threaten prison sentences for referring to the invasion as a war — it would be suspending new uploads and livestreams from users in Russia.

Then, something shifted.

According to a report by Tracking Exposed, four days after its announcement, TikTok (along with other Chinese social networking sites, such as Weibo) started banning content critical of Russian president Vladimir Putin. The following day, VICE reported that Russian TikTok influencers are being paid to spread pro-war propaganda.

The Tracking Exposed report revealed that TikTok was effectively turned into a propaganda dissemination vector by the Kremlin government. All content from European and American accounts was restricted: to a user in Russia, it’s as if it never existed. By Tracking Exposed’s estimation, 95% of all TikTok content was rendered inaccessible from Russia.

So what remained? Pro-Putin content is abundant, as are videos praising Belarussian president Aleksandr Lukashenka. Memes disparaging Ukrainian president Zelenskyy are also common, often containing homophobic themes.

Crucially, an organised network of influencers was identified. Despite the new content ban, their ability to post videos was unhampered. These videos were all uniformly pro-Russian.

Chapter 7 Fighting disinformation: what is to be done?

We have to be honest: things look bleak. Social media, which was never a trustworthy source of news in the first place, is being gamed for political gain. The operators of these networks are reluctant — and often explicitly unwilling — to take action against known bad actors.

On one front, traditional news media is losing ground to partisan organisations relying on inflammatory content. On the other, it is neutered by its billionaire owners with vested political interests.

Who, then, can be trusted? This is where new media steps up to the plate. While the internet can be used to spread disinformation, it also lets us verify facts incredibly quickly. Fact-checking websites and organisations such as Snopes and Politifact specialise in monitoring discourse trends and hot topics — and debunking lies, if necessary.

Some new media organisations, such as Bellingcat, devote themselves to open investigative journalism. Their approach aims to be as transparent as possible, often posting detailed guides explaining their methodology and approach. The tools they use to conduct their research are listed on their website and freely available to anyone.

The Bellingcat Online Investigation Toolkit contains masses of collected online tools, resources and apps to assist you in your own open source investigations https://t.co/qii8i4eoqf pic.twitter.com/r6Nudx63N4

— Bellingcat (@bellingcat) June 2, 2021

Carefully choosing trustworthy news sources — and knowing the biases held by others — only does so much, however. As long as social media platforms are allowed to remain as they are, letting disinformation and hate speech thrive in the name of disinformation and profits, they will remain a danger. Thus, two scenarios present themselves: either these companies become subject to heavy international regulation, or we simply divest ourselves from them.

According to a Pew Research study conducted in 2021, the amount of Americans getting their news from social media is shrinking. This is good news for Americans — but they are an outlier. Plenty of people around the world depend on Facebook for internet connectivity, period. During the 2010s, Facebook heavily invested into building internet infrastructure in developing countries, effectively becoming the primary internet service provider.

To people living in those countries, it’s Facebook or nothing at all — and that puts the platform in a uniquely powerful position. At the end of the day, it’s Mark Zuckerberg who decides what content those countries can access. Any attempt at regulating his power can be met with a threat of turning off connectivity for millions of people — how are you supposed to negotiate with someone this powerful?

Heavy regulation will come down, sooner or later. Perhaps then we can have some of the old internet back: when all sites like Facebook were for was sharing pictures of our cats. When content didn’t have to be written to satisfy some nebulous algorithm. When hate speech didn’t have such an easy way of spreading across the world.

Wouldn’t that be something?

Until that happens, however, all of us in the social media space have a shared responsibility. Whether we’re regular social media users, companies advertising on social media, community managers — all of us need to put pressure on both legislators and platform holders to recognise the scale of the issue and to take appropriate action.

Written by Mathilda Hartnell