Table of contents

- Problem Statement

- A Brief History of Disinformation

- The beginning of COVID-19 conspiracy theories

- When conspiracies get big

- Social media is broken

- Why are conspiracy theories so popular?

- What are we to do?

Chapter 1 Problem Statement

2020 will always be remembered as the year of the COVID-19 pandemic – the impact it has had on the entire world can’t be overstated. Most of us spent the year in self-isolation, business has accelerated its shift to online sales models and scientists all over the world have been hard at work fighting the disease.

As with any major global event, however, there has been a lot of misinformation going around. Conspiracy theories and fake news have spread like wildfire. COVID-19 denialism has been one of the biggest problems stopping the world from dealing with the disease. Even heads of state, such as Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro have been downplaying the seriousness of the situation.

Chapter 2 A Brief History of Disinformation

This situation provides us with a rather grim opportunity to discuss how much of a problem disinformation – after all, conspiracy theories and hoaxes have been “a thing” for much of history. Wikipedia claims the “Drummer of Tedworth” as one of the earliest recorded hoaxes, dating back to the 17th century.

Hoaxes, conspiracy theories and misinformation became an useful tool for political oppression – the Salem witch trials almost certainly didn’t convict any actual witches, for instance. That’s not to say all hoaxes are inherently political, however!

In the twentieth century, hoaxes and conspiracies became an international pastime. They ranged from rather quaint and harmless claims: the famous “Paul is Dead” theory claimed Paul McCartney of the Beatles died in a car crash and was replaced by a lookalike – with clues leading to the truth supposedly hidden in different Beatles songs.

It is at this point that we should explain the difference between a conspiracy theory and a hoax. Hoaxes are simple, but deliberate fabrications designed to masquerade as the truth. Conspiracy theories are much more complex – often political in theme.

The difference between the two is best explained with a comparison: the claim that Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon” was recorded to sync up perfectly with 1939’s “The Wizard of Oz” is a hoax. Claiming that NASA employed Stanley Kubrick to fake the moon landing to beat the Soviets is a conspiracy theory.

Like we mentioned earlier, the 20th century is rife with examples of conspiracy theories. This trend only accelerated with the proliferation of the internet and social media in particular – 9/11 trutherism proved that any grifter can launch a lucrative career spreading misinformation.

These days, spreading misinformation and conspiracies online can be a full-time career for many. Look no further than Alex Jones, who spent the better part of the 2010s claiming that shootings, such as the one in Sandy Hook Elementary School, were staged attacks. This – briefly – brought him a lot of attention and sponsorship money.

Chapter 3 The beginning of COVID-19 conspiracy theories

With this in mind, it’s easy to understand where COVID-19 comes from – it’s simply another global phenomenon for conspiracy theory peddlers to attach themselves to. As the crisis escalated and scientists kept working on figuring out the true nature of the virus, grifters competed to outdo themselves to see who could come up with a more ridiculous conspiracy.

Here’s a sampling of some of the most popular conspiracy theories from that period.

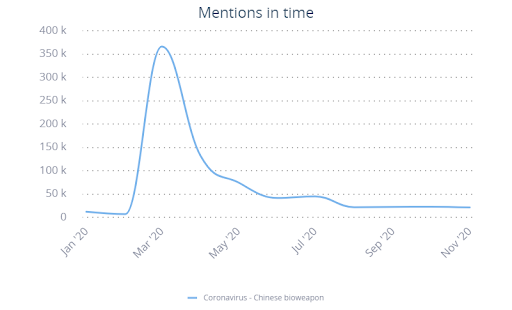

Chinese bioweapon

The first conspiracy theories started almost immediately after the news of the virus were disclosed. These ranged from unfounded claims that the virus was engineered as a bioweapon in a Chinese laboratory (it wasn’t). This theory found some “success” in march, but quickly dropped off – by the latter part of the year, it lost most of its appeal.

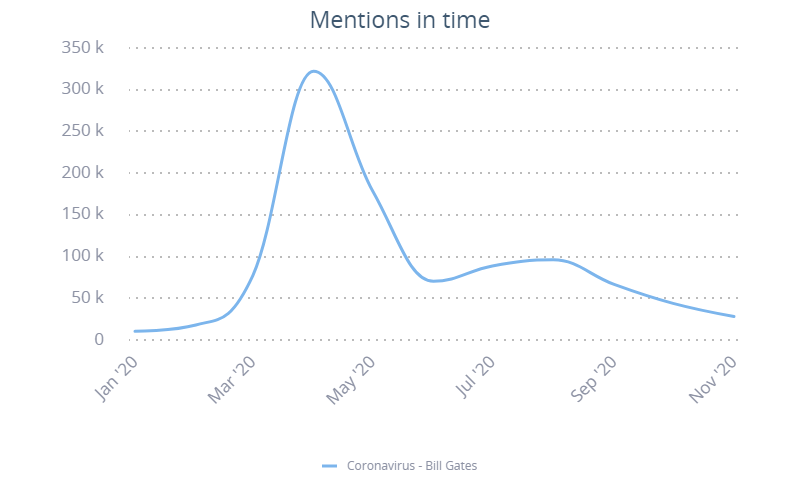

Bill Gates, master eugenicist

This theory claims that COVID-19 was created by Bill Gates as a population control measure (it wasn’t). Bill Gates and his Gates Foundation has been the target of criticism for years, which attracted no small amount of conspiracy theorists to latch onto the subject. A prominent conspiracy theory, debunked by Snopes, claimed that Bill Gates was using vaccines to “depopulate” the world. Since we’re all anxiously awaiting a COVID-19 vaccine, it’s easy to see how this tired conspiracy theory found a fresh breath of life here – if only for a brief moment.

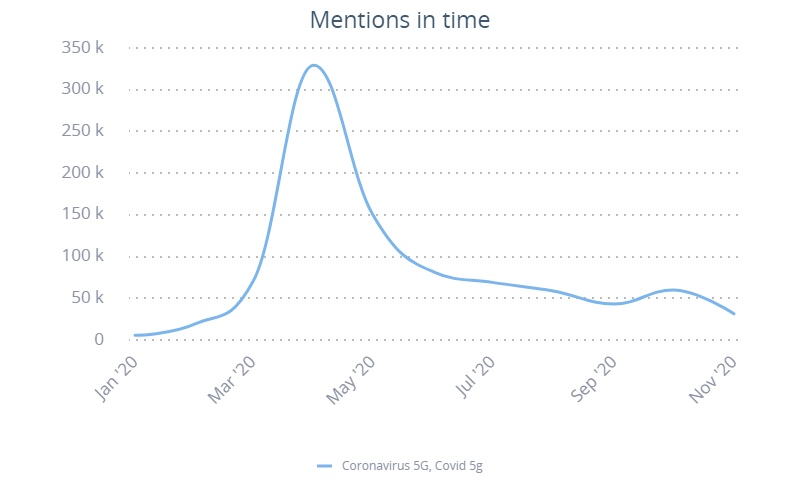

Coronavirus is actually 5G radiation

This is one of the most outlandish theories: it purports that the coronavirus doesn’t exist and the disease’s symptoms are actually caused by 5G towers (it does exist, and 5G doesn’t have adverse health effects). Irrational fears over 5G and other wireless technologies have accompanied us for years – once coronavirus conspiracy theories started flying around, people soon started burning down 5G towers. As is the case with other conspiracy theories, it seems to have died down in recent months.

Chapter 4 When conspiracies get big

Some conspiracy theories got big enough that they started evolving into bona-fide movements. These are especially dangerous – believing a good yarn is one thing, but letting it influence your actions is something else entirely. We’re experiencing a dangerous pandemic – and yet, these people are so deluded that they would willingly endanger themselves and others, disregarding any evidence.

#Plandemic

Among the first widely-circulated pieces of conspiracy media related to COVID-19 was the Plandemic series of videos. These videos, featuring a widely-discredited anti-vaccine researcher and activist and produced by a known conspiracist, achieved a minor degree of virality. Because of that, several – disproven, of course – claims from the video have had a significant impact on the public discourse around COVID-19.

The claims ranged from the virus being purposefully manipulated in a laboratory setting (it wasn’t) to that hydroxychloroquine is an effective treatment (it isn’t, and it can actually make the disease worse). The latter claim is particularly notable – since even president Trump repeated it to his followers.

The viral spread of these claims is particularly troubling – the videos themselves have fallen off, but their effects still haunt us to this day. It’s as Sir Terry Pratchett said: “a lie could run around the world before the truth got its boots on.”

The anti-mask movement

One of the simplest and most effective methods of stopping the spread of COVID-19 has been wearing masks. They serve a twofold purpose: not only do they stop people from infecting themselves through airborne particles, they also stop asymptomatic carriers from spreading the virus further.

So of course there’s people arguing that wearing a mask limits their freedom or constitutional rights et cetera. They would rather endanger themselves and those around them simply because they can’t be bothered to put a simple piece of cloth on.

Studies have shown that the people who exhibit this rather inconsiderate behaviour overlap heavily with the anti-vaccine movement – they mistrust or misrepresent science in the name of “personal liberty”.

At first, the anti-mask movement manifested mostly in the widely-ridiculed public “meltdowns”, but they have recently graduated to large protests. You can see where this is going – hundreds of people, willfully ignoring safety measures? Whatever could go wrong?

Chapter 6 Why are conspiracy theories so popular?

It’s also worth considering why people believe in conspiracies in the first place. Psychologists and sociologists have tried to explain this behaviour for decades. The issue is complex – it’s not just simple paranoid ideation. Many people who believe in conspiracy theories are for all intents and purposes “sane”.

Conspiracy theories often present a “complete” understanding of a given phenomenon, even if it is based on “facts” that don’t stand up to any amount of scrutiny. Circular reasoning also plays a critical role – the lack of evidence is often brought up as proof of conspiracy. When confronted with a debunking, conspiracy adherents often just jump to another bit of “proof”.

It’s also easier to jump onto a conspiracy theory when it provides an “easy” and “quick” answer. Actual science is slow, because it’s required to follow a certain rigor: facts must be checked, theses must be tested and verified, results need confirmation. This takes time: much more time than is necessary to spin a good yarn about how the evil Chinese are spreading bioweapons.

Chapter 7 What are we to do?

Tech giants, such as Facebook, Twitter and Youtube have started taking steps to stop the spread of misinformation – sometimes with mixed results. Posts spreading fake news have their spread and engagement limited. Recommendation algorithms are also tweaked to promote less extremist content – not just with regards to COVID-19, but conspiracy theories like QAnon, too.

This, however, is not a cure-all. There’s simply too much data to sift through in real-time. Machine learning solutions are required, and it’s going to take a long time before they’re able to fact-check everything that goes through the pipeline.

Unfortunately, as we mentioned before, social media is predicated on the quantity-over-quality model. This is an aspect that is unlikely to change – after all, money makes the world go round. As long as there are shareholders to satisfy, anything that risks upsetting the bottom line is unlikely to happen.

While we’re on the topic of money: let’s talk about medical publishing. This is a long-criticised line of business that – in all honesty – should not be a thing. Most research papers are paywalled behind subscription services. “The Great Paywall of Academia” is the reason many of us don’t have easy access to scientific research. At prices such as $40 per article, who could be bothered to “do their own research”?

You may have even stumbled upon this paywall yourself while reading this very whitepaper – by its very nature, we’re forced to link to research and papers, but reading them often requires access to entire publishing libraries, often at a steep price.

Open Access is the idea that all scientific research should be freely accessible to anyone who wants it – it’s what the World Wide Web was explicitly invented for! Unfortunately, greedy publishers are fiercely defending their right to paywall taxpayer-funded research, as the tragic tale of Aaron Swartz reminds us.

Fortunately, his fight to make science accessible to everyone is carried on by people such as Alexandra Elbakyan and her SciHub project. Unfortunately, this is a long and protracted process – toppling outdated copyright laws won’t happen overnight. Meanwhile, misinformation continues to run rampant.

Fortunately, it’s not all doom and gloom – popular science is, thankfully, still a thing. Many doctors and scientists have turned to social media and became influencers in their own right, fighting misinformation with facts.

Put simply, we need to be more proactive and speak out whenever we see misinformation online. Many social networking sites have policies against misinformation and fake news – read them and report posts that spread misinformation and engage more with trustworthy sources. Educate yourself and your peers – it might be difficult and exhausting, but the alternative is much, much worse.

Fortunately, you’re not left to your own devices when it comes to fact checking. Facebook allows you to report false information, which is then independently verified by third party fact-checkers. Google provides an easy, yet powerful fact-checking tool, and Snopes remains a great resource for debunking any hoaxes and conspiracy theories.

Written by Mathilda Hartnell

Chapter 5 Social media is broken

The sad fact of the matter is that social media conditioned us to uncritically consume any information coming our way. It’s easy to forget, but social media platforms are a business first and foremost, and they rather quickly discovered that the more content they serve, the better their profit margin. Quantity over quality quickly became the law of the land. In an environment like that, misinformation thrives.

There’s also a question of psychology. We react to negative and outrageous news in a visceral, highly emotional way. It’s practically addictive – and that’s reflected in the engagement metrics on posts which elicit these emotions.

This, in turn, helps train the recommendation algorithms on social media platforms; they end up serving more and more posts like that. Pretty soon, users get overwhelmed with misinformation.

This phenomenon was at the heart of a recent controversy at YouTube – where its recommendation algorithm was found to function as an excellent radicalisation pipeline by constantly promoting alt-right content.