QAnon Case Study – Fighting Fake News in 2020

Over the last couple of months, major social networking sites have announced that they would be banning all content related to QAnon, the popular conspiracy theory, from their platforms.

To some, this is welcome news, if long overdue; others may not be even aware of what QAnon is and why it warrants such a decisive response. To make sure we’re all up to speed, let’s take a moment to learn what this whole QAnon thing is all about.

A brief history of QAnon

QAnon is a far-right conspiracy theory initially started on the infamous anonymous message board 4chan, later moving to its current home at 8kun (formerly 8chan). It evolved out of earlier conspiracy theories, such as Pizzagate, and largely follows the same themes.

To wit, a prominent global cabal of politicians and celebrities is purportedly engaged in satanism and child sex trafficking. According to the theory, the only forces fighting against the cabal are US president Donald Trump and the eponymous “Q”, the mysterious person – or people – behind the “revelations”.

Supporters of President Donald Trump hold up their phones with messages referring to the QAnon conspiracy theory at a campaign rally at Las Vegas on February 21, 2020. Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images

Q communicates with their followers through “drops” – short, cryptic posts on an anonymous message board. The “authenticity” of these postings is verified by a verification mechanism known as “tripcodes”. To date, there have been hundreds of these postings, making vague allusions to the upcoming “Storm” or “Great Awakening”.

The conspiracy theory alleged that many different events would come to pass. As is often the case with these things, Wikipedia has a running laundry list of falsehoods and failed predictions. These range from mundane – by QAnon standards – claims that Mark Zuckerberg would resign from Facebook to outlandish allusions to time travel technology being developed by the Trump government.

What’s remarkable is how zealous the theory’s adherents can be. In June, a Boston man obsessed with the theory kidnapped his family because he was convinced the “Deep State” was following him. This led to a widely publicised car chase livestreamed on social media platforms. Thankfully, no one got hurt, but this is far from the only incident related to the conspiracy theory.

How QAnon spreads through social networks

Although QAnon was initially only limited to messageboards, such as 8kun, three individuals are credited with starting the wider spread of the conspiracy to other social networks – primarily Reddit and YouTube. From there, dozens of social media profiles, podcasts, and YouTube channels started sprouting up.

By December 2017, QAnon was receiving mainstream media attention from mainstream right-wing and far-right figures, such as television hosts Sean Hannity and Roseanne Barr, as well as conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, who at one point claimed to be in personal contact with Q.

Once major public figures started introducing the conspiracy theories to their social media followers, an avalanche effect took place. There are now numerous splinter groups within QAnon, dedicated to particular interpretations of the “drops”.

The rise of online far-right extremism has led to social media networks taking serious steps to combat the spread of such tendencies across the platforms. Calls for such steps have increased dramatically following the Christchurch mosque shootings in April 2019; the perpetrator livestreamed his rampage on Facebook and posted about it extensively on 8kun, the primary message board associated with QAnon.

Starting this year, social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter have taken serious steps to combat the spread of the QAnon conspiracy theory.

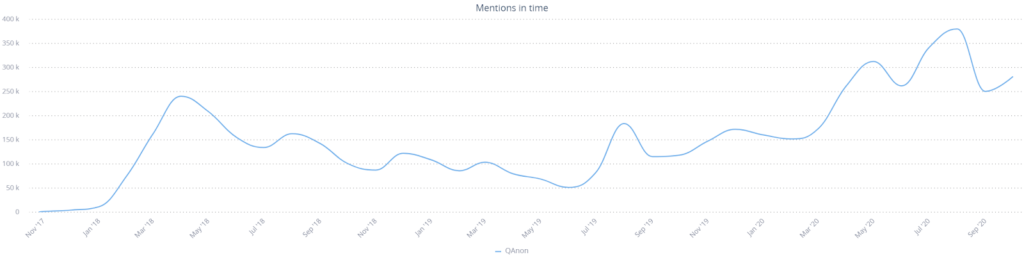

The above graph shows combined Twitter and Facebook mentions for the conspiracy theory. The large dip from August to September this year can be attributed directly to these networks choosing to ban QAnon-related content from their networks.

Twitter got the ball rolling early – all the way back in July. 7,000 accounts have been banned outright, while the initial wave of suspensions is expected to reach 150,000 accounts. Facebook deleted 1,500 groups and pages related to QAnon; they have also modified their recommendations algorithm to stop promoting the conspiracy theory.

YouTube followed suit soon after – announcing in a blog post that they would not only limit the spread of QAnon algorithmically, but that also modify their hate speech and harassment policies to further address the conspiracy theory. Other social media networks are expected to follow suit in the coming months.

This, however, led to the conspiracy’s followers to simply disguise their content by simply not using recognisable keyphrases. Undoubtedly, social platforms will have to turn to using machine learning to detect Q-related posts.

Fighting fake news in the era of social media

The problem doesn’t stop with just QAnon, however. The theory’s followers overlap with other fake news groups – COVID-19 denialists, Flat Earthers, 5G “truthers” et cetera. These conspiracies also will have to be tackled by social media, and it obviously is an uphill battle.

This, in turn, directly ties into the various debates on the influence social media has on our lives, as well as to what extent should social networks be bound by government regulations. While important, these topics fall far beyond the scope of this article – so we’ll leave the reader with the task of doing further research on their own.

We’ll say this, however: there is no denying that social media networks are the primary vector through which fake news spread and cause real harm. The way these platforms present their content to us – quantity over quality. We consume dozens, if not hundreds of tweets and posts every single day. How many of us have the necessary context to approach all of them critically? How many of us just take each post at face value?

While we ponder these questions, let us also consider – how many people do we know that simply don’t believe in the efficacy of face masks in the face of COVID-19, simply because they saw a post on Facebook?

Of course, blaming everything squarely on social media wouldn’t do us any good. There’s a common phrase associated with the 19th century showman P.T. Barnum: there’s a sucker born every minute. Since time immemorial, people have been fooled by cons, “miracle cures” and hoaxes. Naivety is simply part of human nature.

So, what now?

Social media, however, makes the problem exponentially worse. It allows misinformation to spread like wildfire. Of course, we can’t just automatically fact-check every single tweet or Facebook post – there’s simply too many of them.

While the actions taken by major social networks in response to the QAnon conspiracy theory are without a doubt a step in the right direction, there’s still much work to be done. It’ll be years, if not decades, before we figure out how to combat online misinformation – and in the meantime, who can tell how much damage will be done?

In the meantime, every single human being that is capable of logical thinking should use a set of checklists whenever they come across new pieces of information online. Some time ago, we put together a whitepaper on how to recognise and deal with fake news. Stay safe and stay informed.